How to size ESS power and capacity for your company (checklist + examples)

ESS sizing: choose BESS power (kW) and battery capacity (kWh) from your load profile, peak demand, PV surplus and goals like peak shaving and arbitrage.

ESS sizing: how to choose BESS power (kW) and capacity (kWh) for your company (checklist + examples)

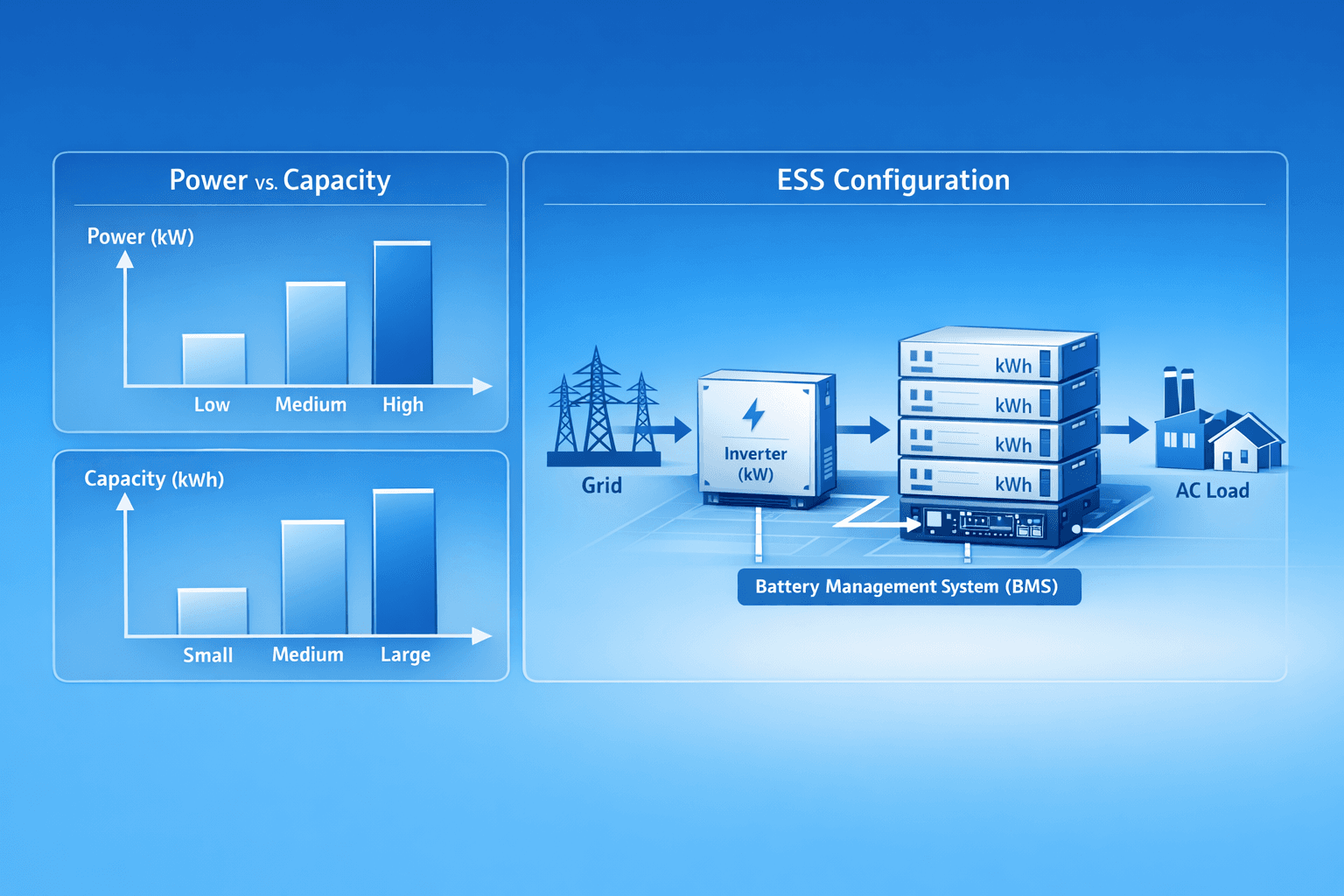

Sizing an ESS/BESS comes down to two numbers: power (kW) to handle your instantaneous peaks and energy capacity (kWh) to sustain discharge for the required time window (peak shaving, time-of-use arbitrage, PV shifting, or backup).

This guide is for energy managers, facility managers, and project engineers who need a practical way to specify battery size without overbuying.

You’ll get a step-by-step ESS sizing checklist, quick rules of thumb, and realistic examples you can replicate using your own interval meter data.

Table of Contents

- kW vs kWh: the 60-second explanation

- Sizing approach: start from the value stream

- Step-by-step ESS sizing checklist (power + capacity)

- How to size BESS power (kW)

- How to size battery capacity (kWh)

- Examples: peak shaving, arbitrage, PV shifting, backup

- Practical constraints: interconnection, space, and permitting

- What data do you need to calculate ROI?

- Why “AI control” matters for sizing

- FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions)

- Summary

- Next steps

- Sources and References

kW vs kWh: the 60-second explanation

Think of kW as the “engine power” and kWh as the “fuel tank”.

- Power (kW) answers: How much load can the battery support at once?

Example: shaving a 300 kW spike for 15 minutes mainly needs kW. - Energy capacity (kWh) answers: How long can it do that?

Example: discharging 300 kW for 2 hours needs 600 kWh (plus losses and reserve).

In commercial ESS sizing, you almost always optimize for a business goal (value stream)—not for “maximum battery size.” A practical framework is to define the goal first, then choose an initial kW/kWh ratio and iterate on historical data (Energy Solutions Solar; DOE Better Buildings).

Sizing approach: start from the value stream

Most companies buy an ESS for one (or two) of the following:

- Peak shaving / demand charge reduction

Reduce measured monthly peak (often 15-min interval) so you pay less for peak demand. - TOU / price arbitrage (day-ahead, intraday, dynamic tariffs)

Charge at cheaper hours, discharge at expensive hours. - PV self-consumption / PV shifting

Store midday PV surplus and use it later. - Backup / resilience

Keep critical loads running for X hours.

Each goal leads to a different “best” balance between BESS power sizing and battery capacity sizing. In simple terms:

- Peak shaving → typically higher kW per kWh (short, sharp events)

- Arbitrage/PV shifting → typically more kWh per kW (longer windows)

- Backup → kW matched to critical load, kWh matched to autonomy hours

Step-by-step ESS sizing checklist (power + capacity)

Use this checklist as a project template. It reflects common commercial sizing phases: define the objective, confirm constraints, simulate, and refine (Energy Solutions Solar; DOE Better Buildings).

1) Define the objective (your “value stream”)

Pick the primary goal and write down the success metric:

- Peak shaving → Target peak reduction (kW) and monthly peak definition (e.g., 15-min max)

- Arbitrage → Target discharge window (hours) and tariff structure (TOU blocks, day-ahead prices)

- PV shifting → expected PV export surplus (kWh/day) and curtailment/self-consumption target

- Backup → Critical loads (kW) and autonomy (hours)

2) Gather at least 12 months of interval data

Best practice is 12–24 months of 15-minute (or hourly) load data, because peaks and seasons matter for sizing (Energy Solutions Solar).

Minimum viable data set:

- Interval load profile (15-min preferred)

- Tariff (energy price + demand charges + fixed fees)

- Contracted/import limit (if applicable)

- PV production (if you have PV) and export limits

3) Identify the “events” you want the ESS to address

Depending on your goal, identify:

- The largest peaks and how often they happen (peak shaving)

- The high-price hours (arbitrage)

- The PV surplus blocks (PV shifting)

A key insight: the optimal system is often smaller than the theoretical maximum, because the “top few peaks” deliver most of the value while additional size adds cost faster than savings.

4) Choose an initial kW/kWh ratio (starting point)

A practical starting point (then simulate and refine):

| Primary goal | Typical discharge duration assumption | What it implies for sizing |

|---|---|---|

| Peak shaving | 0.25–2 hours (often) | Higher kW, moderate kWh |

| Arbitrage / TOU shifting | 2–6+ hours | More kWh per kW |

| PV shifting | 2–8 hours | More kWh; kW depends on ramp rate/load |

| Backup | 1–8+ hours | kW = critical load; kWh = kW × hours |

5) Check technical and site constraints early

Constraints often decide whether your “perfect” size is realistic:

- Point of common coupling (PCC) and interconnection limits

- Transformer/feeder capacity, short-circuit ratings, protection

- Available space and fire safety requirements (setbacks, rated rooms, signage)

Even public guidance documents emphasize that placement and permitting requirements can shape design decisions (City of Palo Alto; City of Covina; Sustainable Energy Action).

6) Run scenario simulations on your historical data

Test a few “discrete sizes” rather than trying to guess the perfect number:

- 300 kW / 600 kWh

- 500 kW / 1,500–2,000 kWh

- 1,000 kW / 2,000–4,000 kWh

This iterative approach is a standard recommendation in commercial right-sizing frameworks (Energy Solutions Solar).

7) Validate warranty and expected duty cycle

Commercial savings depend on cycling pattern. Confirm:

- Allowed cycles/day or throughput warranty

- Limits on depth of discharge (DoD) for warranty conditions

- Expected degradation and end-of-warranty capacity

8) Decide on modularity and “future-proofing”

If you expect expansion (PV, EV chargers, new production line), modular design can reduce risk: start with the most profitable baseline size, then expand later.

How to size BESS power (kW)

Power sizing is mainly about how much you need to reduce or cover instantly.

Peak shaving method (most common in C&I)

- Determine your historic peak demand (e.g., monthly max 15-min kW).

- Define a realistic target peak (often based on contract, transformer, or cost target).

- Compute:

Required BESS power (kW) ≈ Peak (kW) − Target peak (kW)

Example:

- Historic peak: 900 kW

- Target: 700 kW

→ You need ~200 kW of effective discharge power at the meter.

Then add margin for:

- Inverter/PCS limits at temperature

- Round-trip losses (impact is more on kWh, but power derating happens)

- Operational reserve (you may not want to run at 100% DoD)

Arbitrage / TOU method (kW is “how fast you shift”)

For arbitrage, kW is less about clipping peaks and more about how quickly you can:

- Charge in the low-price window

- Discharge in the high-price window

If your high-price window is short (e.g., 2 hours), you need enough kW to move meaningful energy in that time.

A practical sizing check:

- If you plan to discharge E kWh over T hours, then

kW ≈ E / T (again, add margin)

PV self-consumption method (kW tracks PV surplus and ramp)

For PV shifting, the battery power should be able to:

- Absorb PV surplus without curtailment (charge power)

- Support the site load when PV drops (discharge power)

In practice:

- If PV surplus spikes to 250 kW at noon, and you want to capture it, you need similar charge power (subject to export limits and operational strategy).

How to size battery capacity (kWh)

Capacity sizing answers: How many hours of discharge do you need at your target power?

Core formula (with practical adjustments)

Capacity (kWh) ≈ Power to deliver (kW) × Duration (h) / (usable fraction)

Where “usable fraction” accounts for:

- DoD limits you plan to use (e.g., 80–90% usable)

- Round-trip efficiency losses

- Reserve you keep for unexpected peaks or backup

In early-stage sizing, you can use a simple planning factor like:

- Usable fraction ≈ 0.75–0.85 (depending on strategy and warranty targets)

Peak shaving: duration comes from your “peak window”

Do not guess the duration. Measure it from your interval data:

- How long does your site stay above the target threshold?

- Are peaks “spikes” (1–2 intervals) or “plateaus” (1–4 hours)?

A battery that can cover the most valuable peak periods often delivers most of the savings.

Arbitrage/TOU: duration is the high-price block

For TOU shifting, define:

- Discharge window (e.g., 17:00–22:00 = 5 hours)

- How much load you want to offset during that window

Then choose kWh to cover that planned discharge (plus margin).

PV shifting: capacity is “surplus you can’t use right now”

Estimate:

- Average midday PV surplus (kWh/day) across seasons

- How much of it you want to store instead of exporting/curtailing

A strong approach is to size to capture a meaningful share (e.g., 50–80%) of surplus on typical days, not extreme outliers.

Backup: capacity is critical load × autonomy

Backup is the simplest:

- Critical load: 200 kW

- Autonomy: 4 hours

→ 800 kWh usable, then size nameplate higher to keep reserve and meet warranty.

Examples: peak shaving, arbitrage, PV shifting, backup

These are simplified examples to show the sizing logic. Your real answer depends on your tariff, intervals, and constraints—so always verify with modeling (DOE Better Buildings).

Example 1 — Peak shaving for a “spiky” facility

- Historic monthly peak: 800 kW

- Desired cap: 500 kW

- Peak events: typically last 1.5–2.5 hours total per day (not continuous)

Power (kW): 800 − 500 = 300 kW (plus margin → consider 350–400 kW PCS)

Capacity (kWh): 300 kW × 2 h = 600 kWh usable

If usable fraction is 0.8 → nameplate ≈ 750 kWh

Takeaway: Peak shaving is often kW-driven, and a moderate kWh can still deliver high value.

Example 2 — TOU arbitrage with a 4-hour expensive block

- High price window: 18:00–22:00 (4 h)

- Target discharge during window: 250 kW average

Capacity: 250 × 4 = 1,000 kWh usable

At 0.8 usable fraction → 1,250 kWh nameplate

Power: ~250 kW discharge (plus margin), and sufficient charge kW to refill in the cheap window.

Takeaway: Arbitrage is often kWh-driven, because value comes from sustaining discharge through the whole expensive block.

Example 3 — PV self-consumption (store midday surplus)

- PV surplus (typical sunny day): 600 kWh between 11:00–15:00

- Site wants to store most of it, then use it in the evening

Capacity: target 600 kWh usable

At 0.8 usable fraction → 750 kWh nameplate

Power: if surplus peaks at 200 kW, aim for ~200 kW charge power (and similar discharge if evening load needs it)

Takeaway: PV shifting sizing is based on surplus energy (kWh) and the peak surplus rate (kW).

Example 4 — Backup + peak shaving for a small campus

- Critical loads: 200 kW

- Autonomy: 4 hours

- Also wants to shave peaks by 50 kW when possible

Power: at least 200 kW (consider 250 kW to combine backup + shaving)

Capacity: 200 × 4 = 800 kWh usable → ~1,000 kWh nameplate (planning)

Takeaway: For resilience, don’t undersize kWh—backup “hours” are unforgiving.

A quick comparison table (visual shortcut)

| Use case | What sets kW | What sets kWh | Typical risk if wrong |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak shaving | Peak reduction target | Peak duration above threshold | Too little kW → peak not clipped |

| Arbitrage | Needed ramp/shift rate | Hours of high prices | Too little kWh → can’t cover window |

| PV shifting | PV surplus kW and site load | PV surplus kWh/day | Too little kW → curtailment; too little kWh → export/curtailment |

| Backup | Critical load kW | Autonomy hours | Undersize → outage coverage fails |

Practical constraints: interconnection, space, and permitting

Even when sizing from economics, reality is physical and regulatory. Plan for these early:

Interconnection and electrical constraints

Typical checks include:

- PCC import/export limits (to avoid violating contract limits)

- Protection coordination and short-circuit ratings

- Earthing/grounding method and isolation requirements

- Noise/vibration constraints if near offices

Space planning and setbacks

Right-sizing isn’t only financial: site layout can be a limiter. Some commercial guidance notes that a ~1 MW BESS may require a broad footprint range depending on design and site constraints (Energy Solutions Solar).

For placement and permitting, many jurisdictions require setbacks and clear labeling; for example, exterior ESS placement guidance commonly references distances from openings such as doors and windows (Sustainable Energy Action).

Fire safety and documentation expectations

Permitting packages often require clear plans and fire-related documentation for ESS projects (City of Palo Alto; City of Covina).

If you operate internationally: always align with local codes and your insurer’s requirements. Treat “code compliance” as a sizing input—because it can change where and how big the system can be.

What data do you need to calculate ROI?

To accurately calculate energy storage savings, you need:

- Energy consumption profile (hourly or 15-minute intervals) or invoices + interval data

- Tariff / pricing model (fixed vs dynamic)

- Contracted power / peak demand information

- Existing PV installation details (kWp, production, self-consumption)

Why “AI control” matters for sizing

Two companies can install the same kW/kWh system and see different results, because savings depend on dispatch quality (when and how the battery charges/discharges).

AIESS systems are designed for businesses that want zero-maintenance, fully automatic optimization:

- Forecasting of load patterns and peak events

- Automatic scheduling for peak shaving and price windows

- 24/7 monitoring and continuous optimization

In practice, better control can mean you can often achieve the same business goal with a smarter, not bigger system—because you capture the most valuable peaks and avoid “wasting cycles” on low-value operation.

Why AIESS?

AIESS energy storage systems stand out with:

- AI Control - automatic charge/discharge scheduling

- Forecasts - energy prices, weather, load predictions

- 24/7 Monitoring - savings reports and continuous optimization

Common sizing mistakes (and how to avoid them)

- Using only monthly bills instead of interval data

Peak shaving requires seeing the shape of peaks, not just totals. - Sizing to the single worst day of the year

You pay for that size every day, but it earns value rarely. - Forgetting usable capacity (DoD, reserve, losses)

Nameplate kWh is not the same as usable kWh. - Ignoring operational constraints

Interconnection limits and site layout can cap feasible kW. - Not planning for future load changes

EV chargers, HVAC upgrades, or production growth can shift the answer—modularity helps.

FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions)

-

What’s the fastest way to estimate ESS sizing for my facility?

Start with 12 months of 15-minute load data, define your primary goal (peak shaving, arbitrage, PV shifting, or backup), then test 2–3 candidate sizes against history to see savings and constraint fit (DOE Better Buildings). -

Should I size kW first or kWh first?

For peak shaving, size kW first (peak reduction target), then choose kWh from peak duration. For arbitrage/PV shifting, size kWh first (energy to shift), then kW from how quickly you need to charge/discharge. -

How much battery capacity do I really “use” (usable vs nameplate)?

Usually less than the nameplate. You typically keep a reserve and avoid 100% depth of discharge to preserve warranty life; plan with a usable fraction such as ~0.75–0.85 unless your vendor specifies otherwise. -

Do I need PV to justify a commercial ESS?

Not necessarily. Peak shaving and dynamic tariffs can justify storage without PV, but PV often improves ROI by providing cheap on-site energy to shift and by increasing self-consumption. -

How do demand charges affect sizing?

Demand charges make kW reduction valuable. If your tariff penalizes monthly peak demand (often based on 15-minute maxima), shaving even a small number of high peaks can deliver disproportionate savings. -

Can an ESS help if my load profile is fairly flat?

It can, but peak shaving value is usually higher for “spiky” loads. Flat profiles tend to benefit more from arbitrage (if price spreads are strong) or PV shifting. -

What site constraints most often limit battery size?

Interconnection/PCC limits, available space, and fire safety requirements. Placement rules and documentation expectations can materially influence design and location (City of Palo Alto; Sustainable Energy Action). -

How long does a proper sizing study take?

With clean interval data and a clear objective, initial sizing can be done quickly, but validating scenarios, constraints, and ROI typically takes days to a few weeks depending on site complexity and data readiness.

Summary

ESS sizing is a business optimization problem: kW is chosen to hit your peak reduction or shift-rate target, and kWh is chosen to cover the time window where value is created (peak duration, high-price block, PV surplus, or backup autonomy). The most reliable method is to use 12–24 months of interval data, simulate a few candidate sizes, and select the smallest system that consistently captures the highest-value events—while staying within interconnection, space, and permitting constraints.

Next steps

If you want a size recommendation based on your real profile (not generic assumptions), use our calculator:

See size recommendation in calculator →

If you already know your target (peak cap, PV surplus, backup hours) and want a proposal for an AI-controlled, 100% automatic ESS:

Talk to AIESS / view our offer →

Related articles

- What is an energy storage system (ESS)?

- Peak shaving with battery storage: how it works and when it pays off

- Energy arbitrage with BESS: a practical guide for businesses

- Commercial PV + storage: how to increase self-consumption

Sources and References

Article based on data and guidance from:

- Energy Solutions Solar (2025). “How to Right-Size Energy Storage (BESS) for Commercial Facilities.”

https://energysolutions-solar.com/right-size-bess-framework/ - U.S. Department of Energy – Better Buildings (2025). “On-Site Energy Storage Decision Guide” (PDF).

https://betterbuildingssolutioncenter.energy.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/BB%20Energy%20Storage%20Guide.pdf - Sustainable Energy Action (2023–2025). “Where can an energy storage system be located in a building?”

https://sustainableenergyaction.org/ufaq/where-can-an-energy-storage-system-be-located-in-a-building/ - City of Palo Alto (2019, updated 2024). “ESS Submittal Guidelines (with fire requirements)” (PDF).

https://www.cityofpaloalto.org/files/assets/public/development-services/building-division/electrical-guidelines/submittals/ess-submittal_with-fire-requirements_2019-05-03.pdf - City of Covina (2024–2026). “ENERGY STORAGE SYSTEMS Requirements Handout #27” (PDF).

https://covinaca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/27-Handout-Energy-Storage-Systems.pdf

Last updated: January 16, 2026